Will higher risk-weight floors hit covered bond issuance?

Jul 10th, 2014

Regulators in several countries have embarked upon attempts to calm down mortgage and housing markets. Besides limiting maximum LTVs, Sweden and Norway have been increasing risk-weight floors for mortgage assets in recent months.

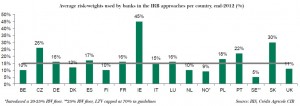

Norway’s move to lift it to around 20-25% is the latest development in this context, which pushes risk-weights well above the levels shown in a European Banking Authority (EBA) study about mortgage risk-weights in the IRB approaches across countries that the regulator published in June. Based on 2012 data, Swedish and Norwegian banks were using the lowest risk-weights, 5% and 9%, respectively. The overall average came in at 15%, thus significantly below the 35% in the standardised approach.

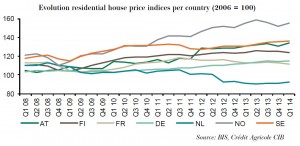

House prices are going up in many countries

House prices in many countries have been rising quite significantly in the last few years. While in many countries this has not yet led to any reactions from regulators, authorities in Nordic countries in particular have begun efforts to calm markets down.

One way in which authorities have been trying to calm down housing and mortgage markets recently is by requiring banks to hold more capital against the mortgages on their balance sheet.

Below, we want to first of all have a look at how mortgage risk-weights differ across countries, and then give our thoughts on what increasing these floors could mean for covered bond issuance from these countries.

The standardised approach:

One size fits all

When it comes to risk-weights on mortgages in the standardised approach, Article 124 of the CRR states that exposures that are secured by a mortgage on immovable property should have a risk-weight of 100%. However, the regulation further says that risk-weights can be reduced to 35%/50% (residential/commercial) if the mortgages comply with the requirements set in Article 125 (residential mortgages) and 126 (commercial mortgages) of the CRR:

Art. 125: “exposures or any part of an exposure fully and completely secured by mortgages on residential property which is or shall be occupied or let by the owner, or the beneficial owner in the case of personal investment companies, shall be assigned a risk-weight of 35%”

Art. 126: “exposures or any part of an exposure fully and completely secured by mortgages on offices or other commercial premises may be assigned a risk-weight of 50%”

Under the IRB approaches:

No two are the same

While all banks using the standardised approach use these figures, the risk-weights used can vary considerably if banks make use of the IRB approaches. Differences across countries (which are understandable to some extent as mortgage markets differ by quality across Europe) but also within countries can be huge.

Getting information on the actual risk-weights used by banks has always been a nightmare. However, the EBA published a document in June analysing the non-defaulted exposure-at-default (EAD) and average risk-weights of 43 European banks. Banks were allowed to use their own definitions for each variable and EBA does mention that it is extremely hard to compare the numbers one-for-one. Nevertheless, we think it is worthwhile to highlight the data as it is the best we have seen on the subject so far.

If we look at the average risk-weights by country, it becomes clear that levels differ in some regions quite significantly to the 35% and 50% used in the standardised approach for residential and commercial mortgages.

Based on December 2012 data, banks on average use a 15% risk-weight in the IRB approach. The lowest figures could at the time be found in Sweden and Norway — the two countries that have very fittingly now introduced floors (more on this below). The only major outlier — apart from small countries such as the Czech Republic or Slovak Republic — is Ireland, where the actual risk-weights used are even higher than the 35% minimum set by the CRR in the standardised approach.

A tool to try to cool mortgage markets?

As mentioned above, Nordic countries have been at the forefront of trying to calm down housing and mortgage markets through regulatory intervention. Sweden has increased mortgage risk-weight floors for banks using IRB approaches a number of times and Norway is now following suit.

- Swedish regulators increased risk-weight floors on mortgages to 15% initially and then further to 25%. This compares to an average risk-weight of Swedish banks of merely 5% at the end of 2012 from the EBA study.

- The Norwegian FSA has announced that Norwegian banks have to increase the probability of default (PD) figures used in their internal model calculations. This will ultimately lead to an increased risk-weight floor of 20%-25% versus the previous 10%-15%.

By increasing risk-weight floors, regulators try to limit the extent to which banks can use their own modelling in the IRB approaches to bring down risk-weights. The idea is to ensure a more level playing field amongst the bigger and smaller banks, at the same time raising the overall amount of capital backing these assets to make sure banks are better equipped to deal with potential problems down the road. Ultimately, higher capital requirements make mortgage lending more expensive and should thus slow down the market.

How does this affect covered bonds?

First of all, the fact that we are talking about risk-weight floor increases (and also LTV ceilings) means one thing: we are no longer talking about covered bond issuance limits. There was a time when the Norwegian authorities were contemplating a limit on covered bond funding to calm down mortgage markets. Imposing limits on an existing market and thus preventing banks from obtaining long term stable funding would not have been ideal, to say the least.

So, moving the discussion over to strengthening capital and lowering high LTV lending to calm down markets is something we welcome.

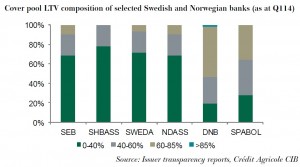

Both of these approaches have no noticeable short term impact on either cover pools or covered bonds. LTV limits apply to new lending only and the composition of a cover pool doesn’t change overnight, especially when covered bond issuance is at the prevailing low level. The higher risk-weights are more likely to prevent banks from paying back “excess” capital to shareholders than to push them to stop lending altogether or even to sell mortgage assets.

These measures can certainly have longer term impacts on covered bonds, however:

- If they reach the goal they set out to achieve, mortgage origination and subsequently also covered bond issuance will be lower than in the past (unless we’re talking about a proper crash, which could drive issuers’ funding mix towards covered bonds).

- Higher risk-weight floors also lead to better capitalised issuers, which is positive for covered bond investors.

- Lower LTV ceilings lead to a longer term improvement in underlying cover pools. We’re talking about a slow evolution rather than a revolution, but in the long run pools will benefit from this measure

In terms of ratings, Moody’s has already published a statement saying that the stricter capital requirements will be credit positive for banks as well as covered bond issuers as it will help limit house price increases and new mortgage origination.

Looking beyond the Nordics, however, there are very lively discussions around the subject in the UK now and we wouldn’t be surprised if we started hearing more on this from other countries in the coming months and years.

Florian Eichert Senior Covered Bond Analyst Stephan Dorner Covered Bond Analyst Crédit Agricole CIB