How might Norwegian issuers react to any regulatory curbs?

Nov 8th, 2012

Florian Eichert, Senior Covered Bond Analyst at Crédit Agricole CIB, examines the Norwegian FSA’s reasons for applying the brakes to covered bond issuance and considers how Norwegian issuers might react.

After the Swedish central bank requested more transparency on asset encumbrance from their banks at the beginning of October, the Norwegian FSA followed in mid-October. However, while the Swedes were only requesting more transparency, the Norwegian FSA went a step further.

Although the Norwegian FSA highlighted the positive aspects of covered bonds as a stable funding source in difficult times, it also criticised high covered bond usage as a source of increased asset encumbrance. As a consequence, it mentioned the possible introduction of issuance limits on covered bonds or additional capital requirements for those banks with a strong focus on the product.

We have taken the freedom to go through the main criticisms and give our obviously somewhat pro-covered bond biased view.

The Norwegian FSA’s criticism

“When the presumptively best secured loans on banks’ balance sheets are mortgaged, banks’ other creditors, who are unsecured or lack a deposit guarantee, perceive an increased credit risk.”

Loss given defaults (LGD) go up the more assets that are encumbered — correct. But on the other hand, probabilities of default (PDs) go down for issuers that can rely on covered bonds. Low funding costs add to the profitability of the institutions, and that in turn helps senior guys as well. Especially when looking at investment grade issuers with relatively high ratings, PDs are so low that a slight increase in LGDs from additional asset encumbrance doesn’t create a major impact on overall expected losses for senior unsecured creditors in our view. This is obviously different when talking about very weak institutions, but we are not talking about very weak institutions in Norway when looking at the covered bond issuers.

“Banks’ funding opportunities are likely to be vulnerable to changing economic conditions. In periods of rising house prices and demand for home loans, banks have ready access to funding through covered bonds. In downturns accompanied by falling house prices, this funding source may rapidly dry up at the same time as other funding opportunities are weakened because the best loans have been mortgaged. Hence covered bonds may add a detrimental, pro-cyclical element to banks’ funding and lending.”

The only really stable and readily available funding source in times of systemic stress is central bank money in our view. Senior unsecured funding is even more volatile than covered bonds and dries up quicker. Deposits are also anything but stable as could be seen in the case of Northern Rock. So even though covered bonds can add to pro-cyclicality in funding and lending, so does any other source of market funding, senior even more so than covered.

“The fact that home loans can be funded at significantly lower interest rates through covered bonds than is the case with loans to business and industry may, detrimentally, draw bank lending away from businesses towards households.”

Where bank lending is drawn to depends on asset margins as much as it does on funding spreads. If asset margins are attractive enough to compensate for higher unsecured funding costs, banks will go for non-cover pool assets. In addition to this, long term covered bond funding reduces the overall PD of an institution compared with one without access to this product, thus also its senior funding cost and eventually loan pricing in other sectors.

At this point, just two final remarks on the topic of asset encumbrance:

- The biggest source of encumbrance in recent history has been central bank funding, not covered bonds. Unfortunately covered bonds are the most transparent source of encumbrance and have thus been dragged into the spotlight first. Limiting covered bonds will merely lead to other forms of encumbrance by banks (securitising mortgage portfolios and pledging them to the ECB, for example).

- And do authorities really want to push banks over the edge by cutting or limiting collateralised funding that stays on for longer than unsecured funding in times of stress? Had we had encumbrance levels in place in the past already, a number of banks that are still alive and kicking today would have had to close their doors by now.

What will happen now…?

At this point the FSA has merely highlighted the above-mentioned points. On the topic of issuance limits they say the following:

“If general restrictions are to be introduced, this must be done in a way that does not undermine the established market for covered bonds. Regardless of possible general restrictions, Finanstilsynet will focus on the use made of covered bonds when assessing the individual bank’s risk and capital need.”

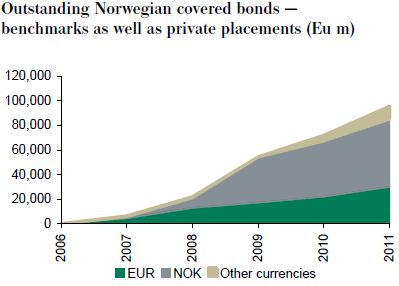

In Norway issuance is done via specialised covered bond banks that are part of universal banking groups. Naturally issuers such as DNB Boligkreditt or Terra BoligKreditt have significant asset encumbrance levels as covered bond funding is literally all they do. But even if we take encumbrance at the group level, figures are fairly high as Norway has a well established covered bond market.

In this situation it is very hard to add issuance limits to an existing market. For now the FSA will rather focus on taking increased encumbrance risk into account by asking banks to potentially hold more capital. This is the same approach the UK or Dutch FSA take these days and it does make sense to look at it that way.

What will issuers do…?

We don’t see how the FSA can add issuance limits to an existing market unless limits are high enough to accommodate at least the status quo. So there will be no need for issuers to, for example, start buying back covered bonds to comply with any rules. We think the impact will be more subtle and differ across issuers.

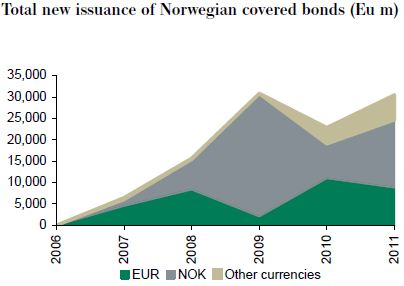

- The increased focus by the Norwegian FSA on asset encumbrance and covered bonds is changing the tone when it comes to future covered bond issuance plans by Norwegian issuers. It could certainly make some issuers think twice about going for covered bond funding in 2013 and make them reconsider their target funding split between covered bonds and unsecured.

- If the FSA proceeds to request additional capital for higher encumbrance levels, this will increase the internal all-in covered bond funding costs for issuers. This in turn will make them tolerate a higher covered-senior spread up to which they prefer to go for senior unsecured funding.

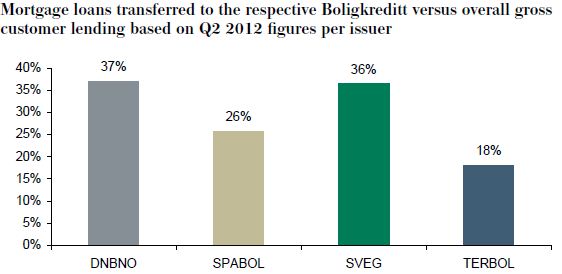

Both of these aspects are, however, something that will not apply to all banks equally. TERBOL or SPABOL should, for example, have more leeway for additional covered bond issuance than, let’s say, DNBNO or SVEG.

Against this backdrop, it looks rather unlikely to us that DNB will repeat 2012’s euro covered bond issuance volumes in 2013 (the issuer successfully issued three jumbo covered bonds in 2012 totalling Eu5.5bn). Norwegian covered bond issuance volumes in 2013 should therefore come in lower than in 2012 and be spread more evenly over a number of issuers than was the case in the past.

Sources: ECBC, Crédit Agricole CIB, banks’ financial reporting